Since I recently did a blog post about the impact of the Seaway on Cornwall, it seems appropriate to do the same for Montreal (note: the following is taken from a paper and presentation about the impact of the St. Lawrence project on both Montreal and Cornwall that I did at an urban rivers conference at the Rachel Carson Center in February 2013; this in turn was largely derived from my forthcoming book, Negotiating a River: Canada, the US, and the Creation of the St. Lawrence Seaway).

Throughout the 20th century there had been a good deal of opposition in Quebec to the Seaway based on the fear that Montreal and Quebec City would by bypassed by river traffic and lose a great deal of their port and transshipment business. While that opposition likely represented a group of specific interests with a great deal of influence, by the early 1950s opinion in the province tended to be that a Seaway would benefit Quebec economically. This tendency was based on belief that Montreal, and the province in general, would benefit from shipping the recently-discovered iron ore in the Ungava region (which straddled the northern Quebec and Labrador border) to the steel factories of the Great Lakes region.[1] A number of companies had joined with the American Hollinger-Hanna group to form the Iron Ore Company of Canada, and this conglomeration of U.S. interests signed a development deal with Quebec in 1951, helping pave the way for commencement in 1954 of the long-delayed St. Lawrence Seaway and Power Project.[2]

The St. Lawrence had dictated Montreal’s spatial development since the city’s inception.[3] The Seaway aspect had a greater direct impact on Montreal than did the power project, given that the hydro-electric aspect of the dual project (and the concomitant flooding) was located to the west. That is not to say that changing the water regime in the international stretch of the St. Lawrence (i.e. the part of the river bordered by New York State and the Province of Ontario) for power development could not affect water levels at Montreal: the changes to the St. Lawrence upstream would have affected Montreal’s water levels had the two countries not built control works in the international section of the river and established methods of regulation to govern the water regimes of the St. Lawrence and Lake Ontario. The regulation criteria outlined that the water level of Montreal Harbour would be no lower than would have occurred if the power project had not been built.[4] As far as the canalization aspect of the dual project was concerned, the Montreal area involved the most work and most expense, in no small part because of all the changes required to the infrastructure around and over the river.

SLSA blueprints from 1950s. © Library and Archives Canada

Map of the St. Lawrence Seaway channel and dike © Daniel Macfarlane 2013.

The St. Lawrence project required the acquisition of a great deal property at Montreal. Until the early 1950s engineering plans had generally called for the Seaway channel at Montreal to run along the north shore, and earlier blueprints variously show the navigation channel running alongside Verdun (located west of downtown along the Lachine Rapids) and cutting through neighbourhoods further to the west. But before construction began in 1954 the location of the new deep waterway was shifted to the St. Lawrence’s south shore opposite Montreal. Government authorities had decided that it would be easier and cheaper to build a navigation channel along the south shore because of lower property values and less developed infrastructure. While there is no direct evidence that officials believed that it would be easier to put the Seaway channel near those with less economic and political power, including the Akwesasne Mohawk First Nations reserve, it is difficult to imagine that this was not a prime consideration. Locating the Seaway channel on the south side of the river can be interpreted, alternatively or simultaneously, as an attempt to transfer the costs of development onto more marginalized or less influential communities, or to disperse the benefits of development by bringing industry and development to other areas outside Montreal’s harbour area. The Seaway channel cut directly through the Kahnawake community, severing it from the river. The treatment, and response and resistance by the First Nations communities, make for a fascinating case study.

Vessel in Seaway channel at Kahnawake © Library and Archives Canada

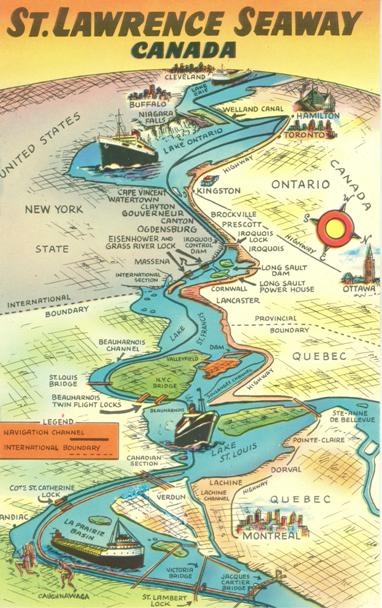

The final Seaway plans placed two locks in the Laprairie basin on the south shore opposite the City of Montreal: directly across from the Montreal harbour was the St. Lambert lock, and at the foot of the Lachine Rapids was the Côte Ste-Catherine lock. Both of the locks were set off from the water by the 18 mile Laprairie dike along the south shore of the river. This was followed by dredged channels through Lake St. Louis and Lake St. Francis, between which were the Beauharnois Canal and its two Seaway locks, and then on through Ontario/New York

Little did Montrealers know that neighhourhoods west of Verdun could have actually met the same fate as the drowned Lost Villages in Ontario. Since at least the 1920s plans for the St. Lawrence project had included a power dam flooding out the Lachine Rapids.[5] In the 1950s, the Canadian government approached Maurice Duplessis, the Union Nationale Premier of Quebec, about developing hydro-electricity from the Lachine Rapids as part of the St. Lawrence project. But Duplessis claimed Quebec did not need this power at the time, as a burgeoning hydro nationalism inspired the province to start other dam developments in hinterland areas of the province, such as the Manicouagan and James Bay hydro projects.[6] For political reasons, the Quebec government also declined to play a role in the Seaway construction, though it did agree to help transportation tunnels under the new Beauharnois locks just west of Montreal. As a result, the Canadian federal government handled all aspects of building the Seaway in that province.

Contemporary view of Seaway at Montreal © stlawrencepiks.com

One of the first orders of Seaway construction in the Montreal area was the acquisition of property for the navigation works. By August 1955, 127 expropriations had taken place on Montreal’s south shore for the Côte Ste-Catherine lock, and over 70 property owners had received compensation.[7] The owners of property taken for the navigation aspect were offered current value plus 10 percent for inconvenience. In addition to relocations, the federal St. Lawrence Seaway Authority constructed collector sewer systems and several modern water intakes. But the municipality of St. Lambert complained, and a formal investigation started in 1958 was the next year extended to include other south shore municipalities that were also dissatisfied, such as Longueuil and St. Hubert.[8] Complaints included the state of the water and sewer systems, the need for a protection wall, and the deprival of “an agreeable view” of the river by fill (e.g., dirt and rock dumped to form canal embankments) that detracted from property values. The digging of the seaway channel also lowered the water table, drying up many wells in the area, so the St. Lawrence Seaway Authority (SLSA) provided temporary water wagons.

In addition to the actual navigation channel, many people were displaced by the numerous transportation infrastructure changes involved in reconfiguring the St. Lawrence basin. At Montreal a number of bridges needed to have 120-foot clearance for vessels. Achieving the requisite height required a number of engineering breakthroughs.[9] The SLSA was only obliged to build lift spans for Montreal, but realized that non-stationary vehicle crossings (e.g., lift spans) would induce unacceptable traffic blockages. The whole southern part of the Jacques Cartier bridge was raised 80 feet through an innovative jacking system, and in October 1957 a new span was inserted into the bridge.[10] This process attracted engineers from around the world, and was done with a minimal interruption to traffic. The Victoria bridge was given a Y-configuration splitting the bridge with two vertical lift spans on each side of the St. Lambert lock. A new elevated span and approaches were added to the Mercier bridge. The city’s harbour received an expensive upgrade and facelift, including new grain elevators, wharves, piers, and sheds (over time, Montreal’s industrial harbour facilities moved further east away from the Old Port, which eventually become oriented more towards recreation activities in the decades after the inauguration of the Seaway[11]). Three bridges over the Beauharnois canal were given movable spans, and a four-lane highway tunnel was built under the Beauharnois locks.

Vessel in Seaway lock

According to geographer Jean-Claude Robert, the Seaway era “marked the permanent ascendance of truck transport over rail. However, while the railways had always essentially replicated and bolstered the river and shore axes, roads and highways tended to break loose from them. For Montreal, this entailed a loss of interest in the traditional space-structuring axes like the Lachine Canal, the riverfront, and the railway tracks.”[12] The Seaway mediated this spatial transportation transformation, accelerating the population, urban, and commercial growth of the south shore municipalities, as many industries quickly opened in these communities, furthering their integration with the Island of Montreal.

Robert further contends that, nowadays, one “can almost say that Montrealers perceive the impact of the river on the city to be mostly limited to traffic jams caused by rush hour congestion on road bridges.”[13] Michèle Dagenais identifies as myth the perception that in the postwar era Montrealers became disconnected from the St. Lawrence and turned their backs on it. According to Dagenais, the city and its population have never really been totally separated, though the relationships and forms in which water was present did change over time.[14] While the Seaway did not separate the city from the river fully, the Seaway certainly increased the alienation of the city from the river, privatized the shores, and increased water pollution.[15] Indeed, there were severe ecological consequences, which I address in Negotiating a River; for example, Richard Carignan contends that the St. Lawrence river/seaway at Montreal is essentially now made up three separate rivers or ecosystems defined by differing water flows and qualities.[16]

Despite subsequent claims that the project was a federal government initiative foisted on Quebec and that the Seaway hurt Montreal and Quebec’s economy, studies have tended to show that the Seaway was beneficial for that province’s economic and port interests. In fact, the Montreal region may have actually benefitted economically from the Seaway more than any other Canadian area along the St. Lawrence.[17] While the city certainly lost transshipment business, this seems to have been offset by the rise in container shipping. Montreal and Quebec benefitted from the exploitation of the Ungava iron ore that the Seaway made feasible.

[1] Gennifer Sussman, Quebec and the St. Lawrence Seaway (Montreal: C.D. Howe Institute, 1979), 8; Susan Mann Trofimenkoff, The Dream of Nation: A Social and Intellectual History of Quebec (Toronto: MacMillan of Canada, 1982), 269.

[2] Sussman, Quebec and the St. Lawrence Seaway, 2; 30-2. See also, for example, speeches and reports by municipal officials, such as C.E. Campeau, the Assistant Director of the Montreal City Planning Department. St. Lawrence University Archives, St. Lawrence Seaway Series, Mabee Series (D. Canadian Materials), Box 71, file 6, C.E. Campeau, Assistant Director of the Montreal City Planning Department, “The Saint-Lawrence Seaway and Its Effects on the Montreal Region,” lecture delivered to the Canadian Progress Club of St-Laurent, December 9, 1954.

[3] Other useful works on Montreal include Jean-Claude Marsan, Montreal in Evolution: Historical Analysis of the Development of Montreal’s Architecture and Urban Environment, (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s Press, 1990); John Irwin Cooper, Montreal, a Brief History (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1969); François Dollier de Casson, A History of Montreal 1640-1672 (New York: Dutton & Co., 1928); Paul André Linteau, Histoire de Montréal depuis la Confédération. Deuxième édition augmentée (Montreal: Éditions du Boréal, 2000). Recent works on the environmental history of Montreal include Stéphane Castonguay and Michèle Dagenais, eds. Metropolitan Natures: Environmental Histories of Montreal (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2011); Michèle Dagenais, Montréal et l’eau: Une histoire environnementale (Montréal: Boréal, 2011).

[4] The regulation criteria outlined that the water level of Montreal Harbour would be no lower than would have occurred if the power project had not been built. Bryce, 94; Library and Archives Canada (LAC), RG 25, vol. 6778, file 1268-D-40, pt 43.2, St. Lawrence Seaway and Power Project – General File, DEA Memorandum: Lake Ontario levels, April 26, 1955.

[5] Overtures to the Quebec government accelerated in the late 1940s, and in 1951 the federal cost suggested that the cost to Quebec for the development of approximately 1.2 million horsepower was $235 million. LAC, RG 25, vol. 2636. File: 1268-D-40C: St. Lawrence River-Niagara River Treaty Proposals (General Correspondence) (January 4, 1938 to December 21 1940); LAC, RG 25, vol. 6344. File 1268-D-40, pt 13.1, St. Lawrence & Niagara River Treaty Proposals – General Correspondence. (July 4, 1951-October 13, 1951).

[6] The control of water and nationalization of electricity “was advertised as the ‘key to the kingdom’ that would put the francophone majority of Québec in control of its own territory, industry and development.” C. Hogue, A. Bolduc, and D. Larouche, Québec, un siècle d’électricité (Montréal: Libre Expression, 1979), 277, quoted in Caroline Desbiens ‘Producing North and South: A Political Geography of Hydro Development in Quebec,’ Canadian Geographer 48, no. 2 (2004): 101–18.

[7] LAC, RG 25, vol. 6778, file 1268-D-40, pt 46, St. Lawrence Seaway and Power Project – General File, July 21, 1955 to Sept 30, 1955, SLSA press release #62, August 17, 1955.

[8] LAC, RG 12, vol. 3746, file 11300: Various Claims by South Shore Municipalities Re: The St. Lawrence Seaway; LAC, RG 12, vol. 3746, file 8122-58, St. Lawrence Waterway, Studies Re: Lands & Services of the South Shore Municipalities as Affected by the St. Lawrence Seaway, vol. 2. April 30, 1959.

[9] LAC, RG 25, vol. 6779, file 1268-D-40, pt 50, St. Lawrence Seaway and Power Project – General File, SLSA press release #157, November 11, 1957. The 10 bridges and their bridge types are as follows:

St. Lambert: two vertical lift spans, railway and highway

Côte Ste-Catherine: one rolling lift, highway

Caughnawaga: two vertical lift, railway

Melocheville: one swing span, railway

St. Louis: one vertical lift, railway and highway

Valleyfield: one vertical lift, railway and highway

Iroquois: one rolling lift, highway

Cornwall: one high level suspension bridge, highway

[10] Fifty feet of this amount was provided by actually raising the bridge itself. The remaining 30 feet result from changing the 250 foot span crossing the Seaway channel (between the ninth and tenth pier) from a “deck span” to a “through span.” LAC, RG 25, vol. 6780, file 1268-D-40, vol. 52, St. Lawrence Project General File, Sept 18, 1957 to April 21, 1958, SLSA Press Release #176: New Seaway Span goes into Jacques Cartier Bridge, October 20, 1957.

[11] Robert, 145-159. On the pre-Seaway history of Montreal’s relationships with rivers and water see also Dagenais, Montréal et l’eau; Michele Dagenais, “Montreal and Its Waters: An Entangled History,” in Nadine Klopfer and Christof Mauch, eds., Big Country, Big Issues: Canada’s Environment, Culture, and History,” special issue of Perspectives (2011) no. 4, Rachel Carson Center.

[12] Robert, 155.

[13] Robert, 157.

[14] Dagenais, RCC Perspectives; Dagenais, Montréal et l’eau.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Richard Carignan, Positionner le Quebec dans l’Histoire Environnementale Mondialse/Positioning Quebec in Global Environmental History (conference), Dynamiques écologiques/Ecosystem Dynamics, Panel: Rivières & Fleuves/Rivers, Montreal, Quebec, 3 September 2005.

[17] For example, see Gennifer Sussman, Quebec and the St. Lawrence Seaway (Montreal: C.D. Howe Institute, 1979), 30-2. Even before the completion of the seaway, the McGill-sponsored Montreal Research Council tentatively predicted that the waterway would have a beneficial economic impact on the city: Montreal Research Council, The Impact of the St. Lawrence Seaway on the Montreal Area, (Montreal: Montreal Research Council, McGill University, 1958).